Sports Icon and famed broadcaster of the Masters

Began to find his faith at the 1992 tournament

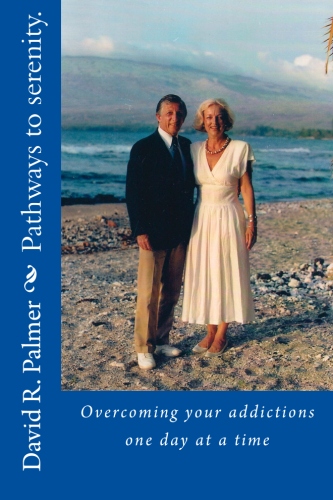

By David Palmer

Pat Summerall died today. He was 82, and it was two days after the end of the 2013 annual Masters golf tournament.

The Masters had a special meaning for Summerall. He had been the voice of the Masters for 24 years on CBS, and it was about to come to an end in 1992. That was when he had his epiphany, that moment of truth when he knew that he was in serious trouble with alcohol.

In a radio interview a couple of years ago with Dennis Rainey, President of FamilyLife, Summerall, a former Arkansas Razorback, New York Giant and premiere broadcaster, described his ghastly confrontation with the truth and his miraculous recovery..

“I was staying in Augusta in a strange house…I had a few drinks before I went to bed, and I got sick. I got up at three in the morning, and I went into the bathroom and threw up, and I looked at—this is kind of gross—but I looked at what had come out of me, and I didn’t realize what it was. It was part of my stomach, and it was blood. And I thought, “what the heck, what’s wrong with me?”

And when Summerall looked in the mirror above the basin, “it illuminated my pale and haggard face, my bloodshot eyes and all the protruding veins on my face and nose.”

He pulled himself together and was able to finish his coverage of the tournament, but the end of his drinking career was at hand. Later that year, an intervention conceived and led by his long time friend, NFL colleague and fellow broadcaster, Tom Brookshire, put him in the Betty Ford clinic in Palm Springs for treatment.

Summerall stayed for 33 days, five more than the usual 28, he says, because it took him five days to get over his resentment against Brookshire and his intervention. He had also been somewhat unsettled at first by the assignment of a roommate whose nickname was “psycho.” But with the help of a “Big Book” and a Bible on his bedside table, he settled in.

Summerall was ultimately grateful for Brookshire’s intervention and stayed in close touch. Since the day he left Betty Ford he never had another drink, and he found a deep faith in God.

So what was it that first launched him down the path of addiction and his close brush with death? Much of his life is described in his 2006 book, “Summerall: On and Off the Air,” and it is full of details about his addiction and recovery and his extraordinary career as a broadcaster.

Summerall grew up in Lake City, Florida. His parents were divorced before he was born, and he was reared mainly by his grandmother, Augusta Georgia Summerall. She loved him and was good to him, and he loved her in return.

As a youngster, Summerall had a crippled leg, and, to her everlasting credit, Augusta saw to it that he had it operated on successfully. In time he became a gifted athlete in high school, college and in the ranks of the pro’s, mostly as a kicker.

His older fans will remember that day in 1958 when Summerall was the kicker for the New York Giants in their NFL championship game against the Baltimore Colts. Highlights are still shown in grainy black and white, and it is still considered by many to be the greatest game ever played.

On that day, the Colts, led by Johnny Unitas, prevailed by a score of 23 to 17 in overtime. Try as they might, Giant fans still cannot stop Colt’s fullback Alan “the horse” Ameche from crossing the goal line and ending the game.

The Giants game against the Cleveland Browns a week earlier to win the division championship, some would say, was even better. The Giants held Jim Brown, among the greatest running backs of all time, in check, and Summerall, after missing a 30-yard field goal, kicked a 50 yarder in a snow storm. The Giants won.

Summerall had entered the pro ranks with Detroit and later joined the Chicago Cardinals before signing on with the Giants. Before joining the pro teams he played both defensive and offensive end for the Arkansas Razorback college team. He also excelled at baseball, basketball, tennis and golf.

In 1961, at the age of 31, Summerall hung up his cleats and accepted a job with CBS in New York City. Over the next 30 years, paired with the likes of Brookshire, John Madden, Chris Schenkle and Jack Buck he prospered. And he drank. Prodigiously. It was vodka in the summer and bourbon in the winter.

And he had lots of company, including Howard Cosell, a broadcaster in his own right and a prodigious drinker who, in Summerall’s company one night, drank more than 14 martinis with barely visible effect.

On another occasion, described in hilarious detail in Summerall’s book, the two of them found themselves stranded in the Bronx late one night. They finally found a cab which they agreed to share with another passenger, a Madison Avenue ad man.

“The adman who was in the backseat with Howard,” Summerall reports, “made it clear that he was not a fan. He’d listened to Howard’s broadcast of the fight that night, [heavyweight Ernie Terrell won] and he made some negative comments about it. The next thing I knew they were swinging away knocking the crap out of each other.”

Summerall stopped the cab and separated them, putting the adman in the back seat and Cosell in the front.

“Howard got in without protest,” Summerall reports, “then slumped over in his seat. His toupee fell off, and I could see a gash in his head.”

The adman took another shot at Cosell when he got out at his home, and when Summerall delivered his friend to his house, his wife asked what had happened, and Summerall replied “Oh nothing, just the usual trip home.”

Summerall loved his work as a broadcaster.

In his radio interview with Rainey, he said, “I think the happiest times, were certainly with Madden and Brookshire. Tom and I, both being ex players became very close friends—like brothers almost-I never had a brother. But he and I became very close. He was the best man at my wedding. We still talk on a weekly basis.

He was a good provider, but Summerall is quick to acknowledge his shortcomings when it came to his late wife, Kathy, and his children Susie, Jay and Kyle.

“I was not a very good father. My relationships with them, my three children and my wife, deteriorated and began to fall apart. I didn’t realize it. I didn’t want to admit it to myself that I was not a very good father… My life was on the road, and I became less and less of a father, less and less of a husband, and I didn’t realize what was happening to me. Maybe I did realize and didn’t want to admit it to myself. I think that’s a better description.”

During his career, he was rarely confronted about his heavy drinking, but one exception was at the Kemper Open.

“I remember one of the wives took me aside. I’ll never forget it. She said, ‘Hey. You don’t have to be the first guy at the dance. You don’t have to be the last guy to leave the party, you don’t have to drink the most, you don’t have to be the life of the party every night. Why don’t you slow down a little bit?’” It didn’t stop him. not then, at least.

After Summerall left Betty Ford, he began to turn his attention to helping others, including his old friend and drinking buddy, legendary New York Yankee baseball player, Mickey Mantle.

Summerall and Mantle had been pals and drinking buddies going back to when they had adjoining lockers in Yankee stadium, where the Giants and Yankees played their home games.

Shortly after Summerall got out of Betty Ford, Mantle pressed him for details on the experience.

“Are they big into religion out there?” he asked.

“Well, yeah—it’s part of it.” Summerall answered

When Summerall asked him about what denomination he was, Mantle had no idea what that meant with the explanation that “I ain’t never been to church.”

“Being from Oklahoma,” Summerall said, “you probably are a Baptist. “

To which Mantle replied, “That’ll be fine. I’ll take that.”

In December 1993 Mantle checked in to Betty Ford.

In early 1995, Summerall says, “Mickey was diagnosed with liver cancer. He was admitted to Baylor University Medical Center in late May of that year and then approved to get on a transplant list.

“Unfortunately, the transplant did not restore Mickey’s health.” Summerall says, “and on August 13, 1995 my dear friend died at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.”

Summerall mourned the loss, but he says, “I was glad for one thing that happened to Mickey after he became sober. Despite his lack of experience with organized religion, Mickey found faith, the things he heard at the Betty Ford Center and from visits from his old Yankee teammate Bobby Richardson led him to God.

“He was baptized and seemed to gain fresh wisdom as well as peace,” Summerall says. “In his last press conference, which he gave at Baylor, Mickey said he was no hero. ‘God gave me everything, and I blew it. For the kids out there, don’t be like me!’”

After more than ten years of sobriety, the physical damage Summerall had done to himself began to surface. Like Mantle, his liver too began to fail and brought him literally to within days, perhaps hours, of dying.

But Summerall got the liver he needed in 2004 when a young man, 13 year old Adron Shelby, son of Melva and Garland Shelby of Pine Bluff Arkansas, died.

“Adron,” Summerall comments in his book, “was just a student in junior high school when he collapsed while giving a speech in history class. He died three days later of a brain aneurysm. A few days after I received their precious gift, the Shelby’s buried their son.

“I talked to Melva from my heart, and thanked her and her family. I expressed condolences for the loss of her son, and I told her what a difference their organ-donation decision had made not only keeping me alive but making me a better person.

“She hugged me again and said, ‘It’s almost like I’m hugging a part of my child.’”

Summerall struggled for some time with the idea that someone—Adron—had to die for him to live. Why did this have to be? The answer, which came from his local pastor, was “because God’s not through with you yet.”

Editor’s note:

Pat’s son, Jay, and Jay’s wife, Kathy, live in Bucks county Pennsylvania near where my son, Michael, teaches tennis at a local club. Michael has been giving lessons to Pat’s grandson, also named Pat, and when Kathy learned of my story of recovery in one of their conversations she suggested we get together.

In early October, I flew to Dallas and drove out to his home on South White Chapel in the fashionable Southlake section of Dallas. From the gate in the towering stone fence bearing the inscription, “Amazing Grace” I could see a winding drive leading, it seemed, to infinity.

Pat’s wife, Cherie, welcomed me on the intercom, the gates swung open, and I drove in. When I pulled up, Pat was standing on the steps of a mansion in a blue shirt and slacks with a black lab, named “Gracie (short for Amazing Grace)” at his side.

After a warm welcome, he led me inside walking a little gingerly, the after affects of hip and knee surgery, and we settled into a couple of easy chairs and Gracie joined us on the couch. I suggested that he tell me what it was like, what happened and what it’s like now. And that’s what he did.

Speak Your Mind